Benchmarking 15-minute cities | Policies for Places

As we saw in my previous post the 15-minute city concept has become the basis for city planning in many cities around the world. It offers a vision of urban living based on compact and complete neighborhoods which are vibrant, convenient, connected and equitable.

Already the 15-minute city is taking on many names and shapes as cities seek to define the form which best suits their aspiration for urban living. This essay is concerned with ways in which cities can assess the extent to which they are making progress towards actually delivering on their aspirations.

Many components make up a 15-minute city. The C40 knowledge hub gives an idea of how cities have prioritized different components as they implement their 15-minute city plans. For example Milan is upgrading streetscapes through open squares and roads program, emphasizing a sustainable urban mobility plan and low speed limits on most of its roads, Melbourne established a Movement and Place framework putting people at the centre of transport planning, Paris is making schools neighborhood ‘capitals’ enabling them to serve multiple functions alongside education and seeking to strengthen local commercial networks, Buenos Aires is aiming to bring green space, food markets, recycling points and health services to every neighborhood and improving walking and cycling infrastructure, whilst Bogota aims to improve the quality of life by improving streets and communities through a series of children’s priority zones centered around childcare centres.

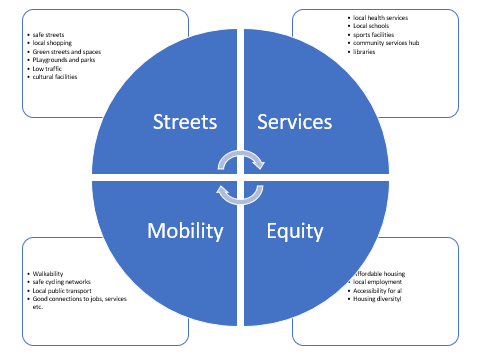

Between them we can identify a number of themes central to the 15-minute city vision. We might characterize these as:

- Street centered;

- Service centered;

- Mobility centered;

- Equity centered

Each of these themes will in itself include many specific actions to secure its own objectives and its contribution to the overall 15-minute city vision. Diagram 1 below illustrates key aspects of each theme.

Assessing progress

Given the wide variety of approaches cities are taking as they implement their version of a 15-minute city and the controversies which abound both of the concept itself and of the form of its implementation, city leaders and policymakers will find it valuable to have some means of assessing progress towards the delivery of the objectives of their 15-minute city programs. It would be better still if it were possible to derive robust research-based assessments from which other city administrations could learn. The complexity of the 15-minute city and their continually evolving nature makes formal controlled evaluation almost impossible. Before-and-After studies are difficult for similar reasons. Clearly some form of measurement is necessary as a basis for the assessment of current performance, the identification of actions needed and to support successful implementation. Here are some possibilities.

Mapping

A basic premise of the 15-minute city is that all citizens have access to a range of features necessary for urban living within 15 minutes travel time on foot, by bike or using public transport. Simple inspection of Google maps will identify areas within a town or city for which this is true, and maybe more importantly, those areas which are underserved by essential amenities. This will help define ‘target areas’ and a reduction in the size of such areas as gaps are filled would be a basic indicator of progress.

There are now apps being developed which will indicate for any location within a city if that location is within 15 minutes active travel time from a given range of facilities. Whilst originally intended to assist developers and individuals searching for properties, it has useful possibilities for city planners too.

Mobility

If mapping technologies such as these can answer basic questions about the spatial distribution of facilities within a city, they can say little about another basic premise of the 15-minute city about living locally. Data is needed about how people ‘use’ the areas in which they live: do they work locally, do they shop locally, do they socialize locally etc. Again whilst it would be possible to conduct diary studies for a representative sample of residents, there are other ‘smarter’ data sources becoming available, such as GPS data from mobile phones, journey-time data from public transport or monitoring data about road usage and mode of transit.

Big Data

Interest in Big Data is growing rapidly as a result of investment in harnessing existing data to address a range of social and health issues and to responding to urban challenges in the lives of citizens relating to such issues as social mobility, transport efficiency, communications and city administration. The term Big Data is used here to refer to vast amounts of information created and stored by private, public and third sector organizations. Such data may include long -standing databases such population and census data, performance data such as educational attainment or health status, but can also include data from social media, street cameras and geographical mapping. The utility of big data will depend on novel methods to capture, analyze and visualize patterns within the data as it emerges.

A benchmarking approach

A fully developed 15-minute city involves and mobilizes a diverse range of stakeholders and resources in what should be a holistic process if its objectives are to be achieved. The assessment of a complex series of inter-related changes is not easy to capture in a set of conventional indexes and survey data. However a benchmarking approach can offer a framework for the analysis of progress in the development of a complex change such as the 15-minute city. It provides a means of ‘mapping’ the strengths and weaknesses of progress in the delivery of aspects of a 15-minute city as a basis for further policy and development. It is possible to design a benchmarking instrument, adaptable to focus on priority issues which provides a structured self-assessment of a wide range of factors central to 15-minute city development and performance, supported where necessary by qualitative data. The application of the benchmarking template should allow the creation of accessible profiles to readily identify those aspects which are well developed and those which require further attention.

A benchmarking template for a 15-minute city

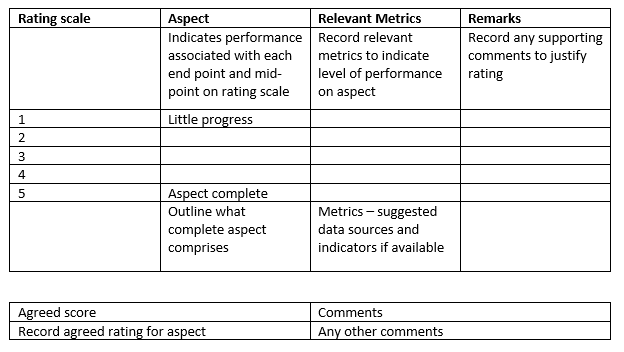

Diagram 1 above could be used as the basis for such a benchmarking template. A crude profile could be drawn looking at performance relating to each of the 4 quadrants in diagram 1. A much more fine-grained profile would result from the assessment of each of the 19 aspects identified within all quadrants. The template consists of appraisal sheets for each aspect of performance which is included in the appraisal. The appraisal sheet could be in the format below, one sheet sheet for each aspect, for example walkability, safe streets, affordable housing or whatever.

The form asks for both qualitative and a limited amount of quantitative data. Each aspect of 15-minute city performance is rated on a 5 pint scale representing a spectrum of performance from little progress to complete provision on that aspect. Stakeholders are asked to self-assess performance on each scale and reach an agreed score. These ratings can never be a precise objective measure but are based on judgements of those making the ranking. The form asks for supporting information to help justify the rating. This may be quantitative indicators of performance or progress against agreed plans or targets.

Data collection can be through several methods, for example through workshops, through the different agencies involved, or through interviews with relevant people carried out by an external assessor.

The data captured by the method adopted can be aggregated to produce a profile of performance for each aspect of the 15-minute city and to examine those aspects where performance is strong or where weaknesses are revealed. A graphical representation of the ratings of each aspect can provide a readily accessible appreciation of the profile obtained.

How good is our 15-minute city?

The resulting analysis can contribute in many ways to the development of policy and practice in taking the 15-minute city concept forward. It can

- Help assess the extent to which city objectives and policies are being delivered;

- Identify strengths and weaknesses in progress;

- Provide qualitative enhancement to more conventional metrics of city performance;

- If repeated over time, monitor changes in performance as policy initiatives are taken forward;

- Assist city promotion through demonstrating progress to external stakeholders and other interests.

Why not try it for you city?

Policies for Places | JOHN TIBBITT | Substack. Subscription is free.

Printer-friendly version

Printer-friendly version- Login to post comments